Guest Blog by Ryan Williams

Trompe l’oeil (‘trick of the eye’)

Ryan J. Williams

How does imprisonment problematize the self? What practices, forms, and techniques do people use to better themselves? To what ends, and with what challenges, do people strive towards some vision of the ‘good’? Whilst serving time in prison, people ask the questions of philosophers and theologians around how they can live virtuous lives – to be better fathers, to live right and well with others, to struggle and strive to ‘make good’. Yet, criminology has largely ignored the ethical character of people’s lives and its sociological significance; comfortable with posing ethical questions about punishment, but rarely investing in understanding the everyday moral lives of those within.

In my recent article on Islamic piety in English high security prisons, I argue for the urgent need to take seriously peoples’ ‘moral projects’ in prison ethnography. The work takes inspiration from literature on moral anthropology and Foucault’s lesser known works (at least among criminologists) on ethical self-cultivation to understand the contours of ethics in everyday life. This approach wrests the philosophical and theological questions from ‘ivory tower’ heights, and seeks to re-examine those questions and allow new ones to be posed in light of the messiness and ordinariness of people’s life experiences in different contexts.

In my recent article on Islamic piety in English high security prisons, I argue for the urgent need to take seriously peoples’ ‘moral projects’ in prison ethnography. The work takes inspiration from literature on moral anthropology and Foucault’s lesser known works (at least among criminologists) on ethical self-cultivation to understand the contours of ethics in everyday life. This approach wrests the philosophical and theological questions from ‘ivory tower’ heights, and seeks to re-examine those questions and allow new ones to be posed in light of the messiness and ordinariness of people’s life experiences in different contexts.

I was drawn to focus on Islamic piety partly due to my academic background and training in religious studies and as a sociologist and anthropologist of religion, and partly because the context demanded it: The Muslim prisoner population was high across the high security estate (some estimates put it at 28%, compared to the national average of Muslims in the community at about 4%), and it was a population that seemed subject to intense scrutiny. My conversations with staff and prisoners referred to the ‘Muslim problem’, which was a phrase difficult to disentangle but seemed to simultaneously refer to problems of quantity (too many of them, like a ‘gang’) and quality (not ‘genuinely Muslim’, in it for the food or protection).

I grew dissatisfied with these summations, and reading criminological accounts of religion and Islam in prison, I grew dissatisfied with those too. Such accounts rendered the efforts of the ethical subject opaque. They totalized empirical description and theorized a self that is merely ‘realized against the institution’, in Cohen and Taylor’s (1972:149) words, rather than allowing for an understanding of how the self is realized within the institution, and thus, of recognizing how people strive to become the types of people they wish to become (even in places as dire as prisons).

In describing some examples of Muslim ethical subjectivity in prison, I focused on the themes of ‘becoming good’ (through study), ‘doing good’ (through acts of kindness), and ‘maximizing the good’ (through efforts to guide others away from an errant path). My argument through these descriptions is not of Muslim exceptionalism, of moralism, or of sentimentalism (in the face of flagrant securitized and racialized tropes around Islam and Muslims – ‘terrorist’, ‘foreigner’). Nor is what I describe intended to essentialize Islam as a universal category of experience and identity. It is rather a case for reflecting on the sociological, even political, significance of piety.

Far from William James’ classic definition of religion as the ‘experiences of individual men in their solitude’, the piety of some Muslim prisoners was expressed externally (through the beard and wearing religious clothing) and relationally (through sharing food), and these became tangled in the complexities of prison social life in ways that were irreducible to categories of coercion, resistance, or radicalisation.

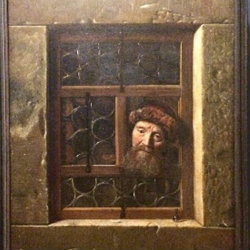

Returning to the cryptic title of this reflection piece, trompe l’oeil or ‘trick of the eye’, and Samuel van Hoogstraten’s marvellous painting, Man at the Window (1653), I have wanted to paint an ethnographic portrait that gives a three-dimensional realism to prison social life through taking seriously people’s various strides to accomplish virtue, and to contextualize this within the local circumstances and relationships of a high security prison. Like the style of painting, though for different reasons, the effect is unsettling.

To read more, see: Ryan J. Williams; Finding Freedom and Rethinking Power: Islamic Piety in English High Security Prisons, The British Journal of Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azx034

Currently, I am developing this work further in two projects: the first enquires into Muslim’s moral lives through imprisonment and post-release, and the second is related to co-convening a course on everyday ethics in a high security prison with University of Cambridge students called ‘The Good and the Good Society’. See here for more details.

Image: Man at the Window by Samuel van Hoogstraten (1653), photo taken by Ryan Williams, Museum of Art History, Vienna