Guest Blog on Challenging life imprisonment

Challenging life imprisonment

By Catherine Appleton and Dirk van Zyl Smit

Life imprisonment is a harsh sanction that gives the state the power to imprison individuals for the remainder of their lives. It is a punishment used in many countries, yet very little is known about how it is imposed and implemented across different jurisdictions. Just over four years ago, we were awarded a grant by the Leverhulme Trust to shed some light on the use of life imprisonment as a global phenomenon, and to assess the practice of life imprisonment across different jurisdictions in the light of fundamental human rights.

We found that formal statutory provision for life imprisonment exists in 183 out of 216 countries and territories, and that in 149 of these it is imposed as the ultimate sanction. Life imprisonment with the possibility of parole is the most common type of life imprisonment in the world: in 144 of the 183 countries that impose formal life sentences, there is some prospect of being considered for release. Sixty-five countries impose the harshest type of life imprisonment, that is, life imprisonment without the possibility of parole (LWOP). Perhaps most surprisingly, there are 33 countries who do not have the death penalty or life imprisonment as a formal statutory sanction.

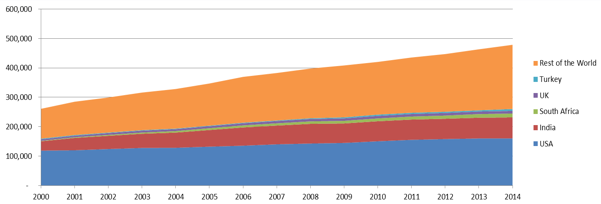

Based on data collected on the number of persons serving life sentences in 114 countries, we were able to estimate that the total number of life-sentenced prisoners around the world has nearly doubled since the year 2000. As of 2014, there were almost half a million – 479,000 – individuals serving formal life sentences. Of significance, five countries have made major contributions to this growth: the USA, India, South Africa, the UK and Turkey. Most strikingly, the USA houses an estimated 40 per cent of the world’s life-sentenced prison population. Furthermore, these figures do not include individuals serving other indeterminate ‘informal’ life sentences, such as very long prison sentences or post-conviction indefinite preventive detention where there is no guarantee of release from prison.

One major concern is the growth in the use of LWOP sentences in the United States. Our research found that more than 50 per cent of all prisoners serving LWOP around the world were in the USA. As reported by The Sentencing Project in 2017, between 1992 and 2016, the number of persons serving LWOP increased by 328 per cent in the USA, from 12,453 individuals imprisoned for life to 53,290. In 2016, every third life-sentenced prisoner in the USA was serving LWOP. While this severe form of life imprisonment has been abolished in most of Europe, other countries, such as India and China, have recently adopted LWOP as a formal statutory sanction. This may lead to a significant increase in the numbers of prisoners sentenced to lifelong imprisonment around the world.

In addition, our research revealed that life-sentenced prisoners are often systematically segregated and treated more harshly than other prisoners on account of their sentence. Many countries, for example, routinely detain life-sentenced prisoners in separate penal colonies, away from the general prison population and under heightened security. Under strict regimes, life-sentenced prisoners are often handcuffed or shackled whenever they leave their cells. They may also be subjected routinely to rub down searchers at all movement times, regular strip searchers, cell searches, video surveillance and restrictions on movement. In some countries, guard dogs have been used to escort life-sentenced prisoners around the prison.

Many life-sentenced prisoners are also excluded from rehabilitative opportunities or denied access to educational and vocational training available to other prisoners. In several countries, the absence of work opportunities is an additional punishment to the life sentence. In such countries, life-sentenced prisoners can spend up to 23 hours a day in their cells with no access to rehabilitation, work programmes, social or psychological assistance.

We also found that, while the pains of imprisonment are well-documented, the impact of life imprisonment is under-researched. Published accounts from life-sentenced prisoners reveal that serving a life sentence is a particularly painful experience due to the uncertainty of release. Doing indeterminate time has been described by different individuals as “a tunnel without light at the end”, “a black hole of pain and anxiety”, “a bad dream, a nightmare” or even, “a slow, torturous death”. Social isolation, futility of existence and fear of institutionalisation are recurring themes among prisoners serving indeterminate prison terms. The pains of serving indeterminate time are significantly heightened for LWOP prisoners, who must come to terms with not only doing very long prison time, but with dying behind bars as they have no hope of release.

But what do the standards say? International human rights standards on imprisonment have developed dramatically in recent years but the issue of life imprisonment has not been addressed sufficiently. The United Nations 1994 report on Life Imprisonment is the only international document that focuses explicitly on life imprisonment. It states that life sentences should be “imposed only when strictly needed to protect society and ensure justice, and… only on individuals who have committed the most serious crimes.” It notes that “it is essential to consider the potentially detrimental effects of life imprisonment”, and proposes, inter alia, that conditions for life-sentenced prisoners should be compatible with human dignity, and that states should provide a possibility for all persons sentenced to life imprisonment to be considered for release.

Some guidance can also be drawn from the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Handbook on the Management of High-Risk Prisoners, and from regional bodies, such as the Council of Europe. In brief, fundamental human rights require states to compensate for the particular pains of life imprisonment, to provide rehabilitative treatment for all life prisoners, not to make life sentences harsher than other prison sentences, and to provide a clear pathway to release.

In our forthcoming book, Life Imprisonment: A Global Human Rights Analysis, to be published by Harvard University Press later this year, we have shown that life imprisonment, in many of the ways that it is imposed and implemented worldwide, infringes some of the most fundamental norms of human rights. To address this injustice we recommend, first and foremost, worldwide abolition of LWOP sentences, together with the abolition of mandatory life sentences. We further recommend that, if life imprisonment is to be imposed, it should be reserved for the most serious crimes, and be compatible with fundamental human rights standards.

In our book we also consider whether life imprisonment should be abolished completely. This may be one solution to the significant increase in life sentences worldwide, and to the impact of the detrimental effects of life imprisonment, not only to individuals in prison but also to the wider community. But it is safe to assume that this is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Together with Penal Reform International we have recently published a short policy briefing on Life Imprisonment. Its objective is to challenge the United Nations and its member states to address the increase of life imprisonment and the implementation of such sentences on human rights grounds. Our hope is that our research will assist the international community in confronting this challenge.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Appleton, C., van Zyl Smit, D., (2018) Challenging life imprisonment. Available at: https://www.compen.crim.cam.ac.uk/Blog/blog-pages-full-versions/guest-blog-on-challenging-life-imprisonment (Accessed [date]).